summertime study (2)

more from Phil Lesh & the Future of the Grateful Dead Songbook

This is the second installment from a talk we gave at the 2025 Grateful Dead Studies Association meeting. The first part, here, includes notes on our research questions, methodology, and 2019 tour/personnel stats. In the third installment, here, we analyze the songbook as played by each band in 2019.

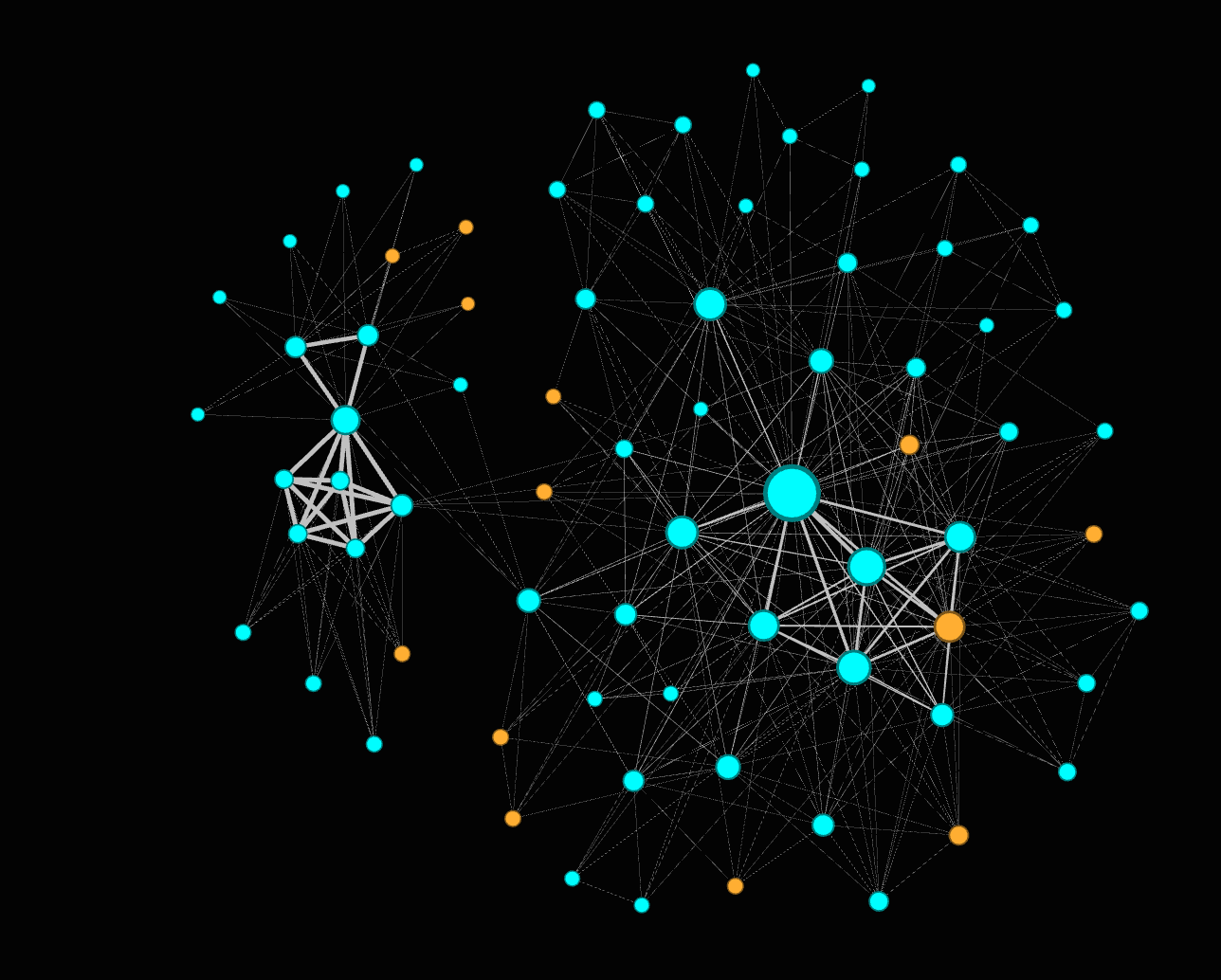

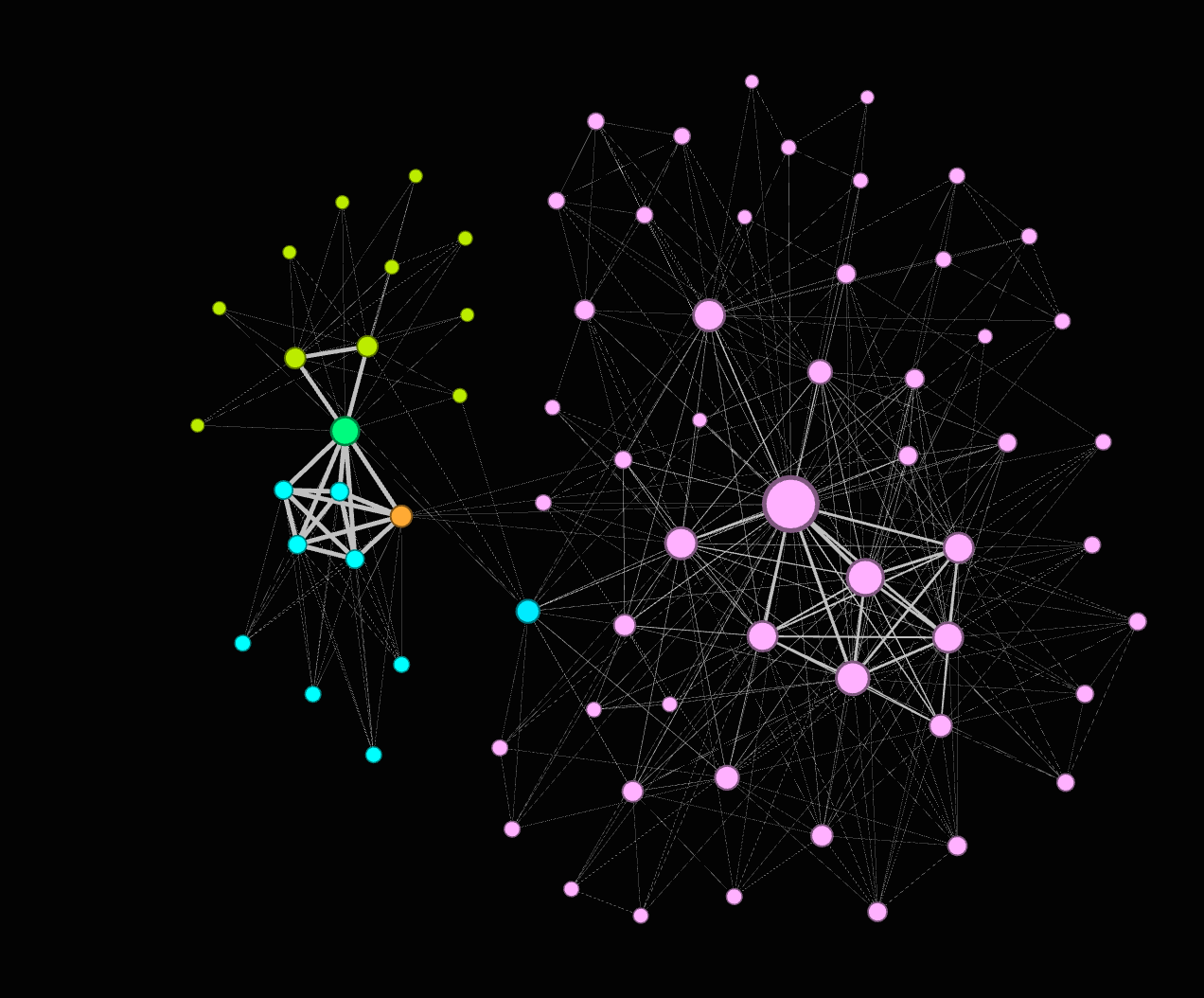

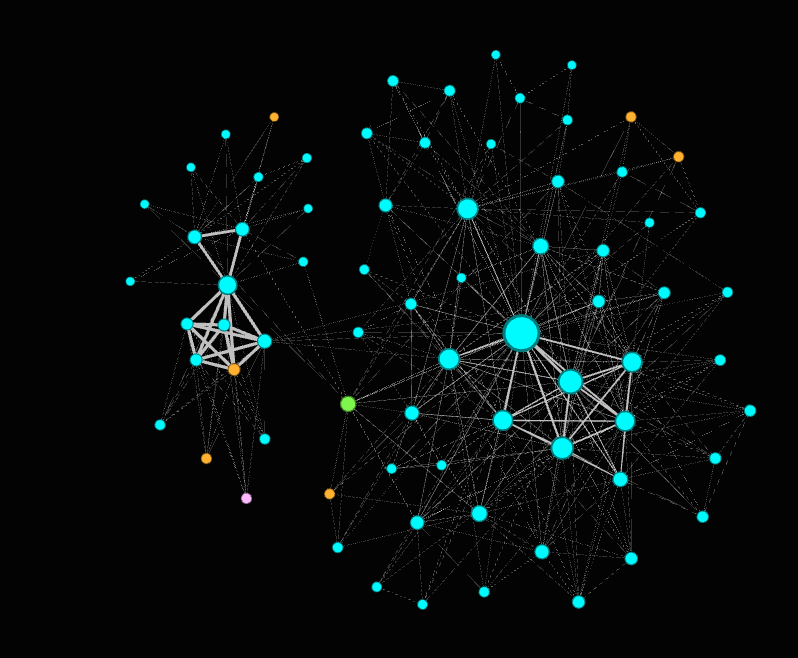

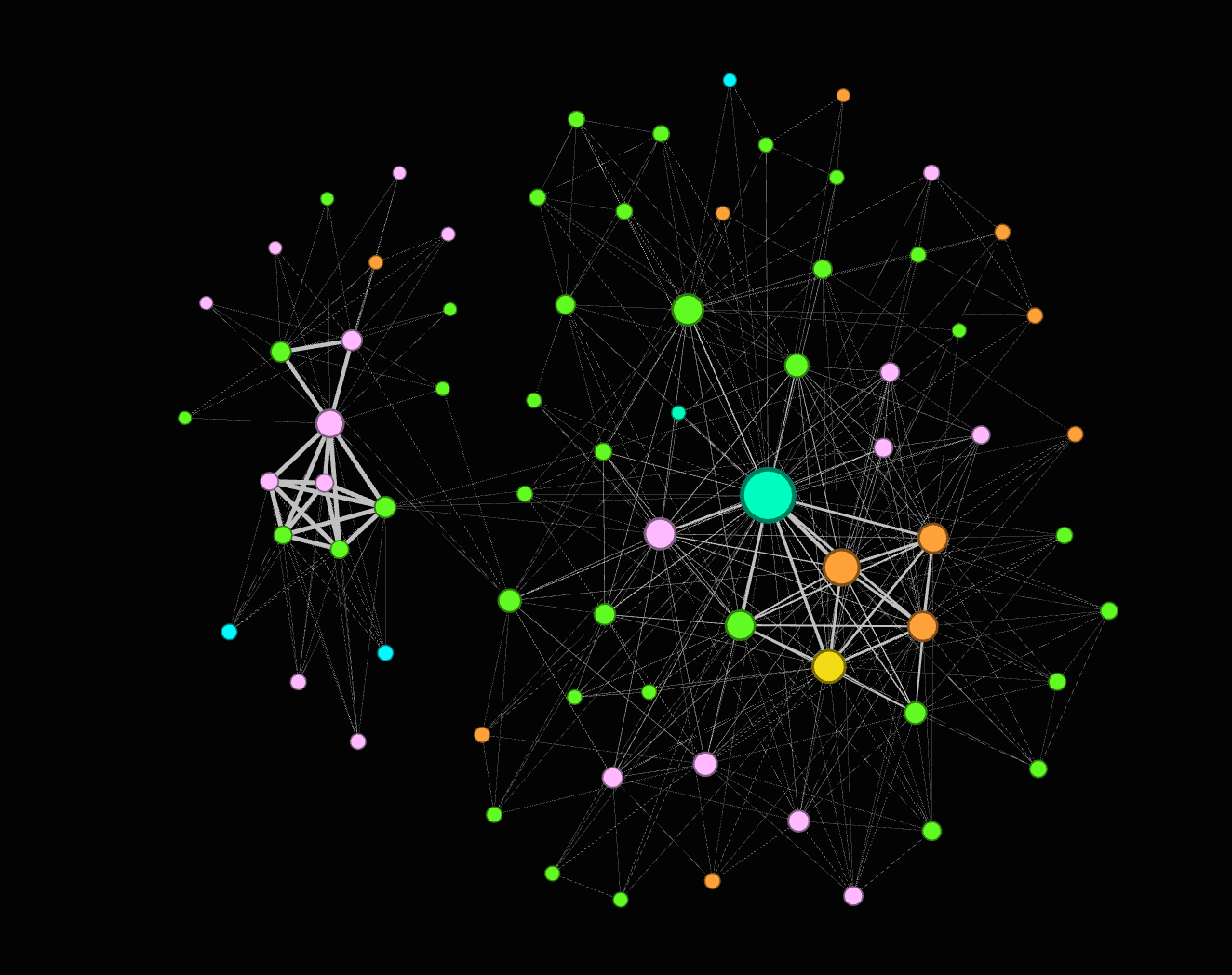

At this point we prepared the personnel data and loaded it into Gephi, an open-source free software platform that visualizes and analyzes the relationships between individuals in social networks.1 We used this tool to better understand the complexity of the three bands we compared—Phil Lesh & Friends, Dead & Company, and Bob Weir and Wolf Bros—including racial, gender, and age demographics for 2019, the year we collected data for. In these visualizations, each node, or dot, is a musician. The thicker the line between two musicians, the more times they played together. Node size reflects how many other musicians each one is connected to in the network.

A note: we are 99% sure that these networks are nowhere near as distinct as they appear when looking at one year of data. If we were to collect similar information for every year that they played, or if we added the same data for Furthur, RatDog, Melvin Seals & JGB, DSO, JRAD, and other bands in this expanding web, we would see more complexity and overlap. That said, we doubt the overall structure of these three networks would change much given each band’s relationship to touring and guests.

The first image depicts the three bands in relation. The visualization here is not too surprising: Dead & Co, the small blue cluster in the lower left, has the tightest lineup and fewest guest appearances. Wolf Bros, the lime green triangle in the upper left, also has a small, stable lineup with slightly more guests. Phil Lesh & Friends, in lavender on the right, appears as a vast galaxy. Phil is the largest node at the center and the cluster of larger dots is the core Terrapin Family band. In 2019 there were almost no overlaps between musicians in the three bands. Only three people appeared in more than one network: Jeff Chimenti (the orange node), Jackie Greene (the turquoise node at the edge of Phil & Friends) and, of course, Bob Weir—the larger, kelly green node that connects Dead & Co to Wolf Bros.

Next we looked at gender. Again, no surprises: this is an overwhelmingly male network. Men are blue and women are orange. The larger orange node in the Phil and Friends network is Elliot Peck who played 19 of 41 shows in 2019. There is slightly greater gender diversity in Phil & Friends but this appears more as a side effect of his much larger network. Here, Wolf Bros begins to look similar to Phil & Friends, with 3 women out of 13 total musicians, or, 23% of the lineup, but Phil & Friends is the only band with a woman in the core lineup.

The next visualization shows racial demographics. As with gender, we see a very homogenous white network. Dead & Co appears slightly more diverse due to the presence of Oteil Burbridge in the core lineup. In this visualization white musicians are blue nodes, Black musicians are orange, the one Asian American musician, Jackie Greene, is lime green, and Zakir Hussein, the one Indian musician, is lavender. Otherwise, these are very white networks. As with gender, Phil & Friends appears marginally more diverse given the larger size of the network. The orange nodes in Phil’s network include Allison Russell, DJ Williams, and Karl Denson.

One thing that interests us here is the way that we mistook our anecdotal experience of seeing more than one woman onstage, or the presence of Stanley Jordan (who didn’t play with Phil & Friends in 2019) as representative of a greater gender and racial diversity than actually exists at scale. This might change slightly if we were to collect data for more years, but even so, we suspect these networks would appear as mostly white, with more men than women.

The thing that did surprise us, which we wouldn’t have seen without collecting and visualizing the data, is the generational diversity of Phil & Friends. In the next image the Silent Generation is turquoise (Phil plus Jorma Kaukonen); Baby Boomers are lavender, and Gen X is lime green. At 83%, Gen X is the largest generational group in all three networks. The orange nodes are Millennial musicians which is where it becomes clear that Phil & Friends skews much younger, including at least one Gen Z player, Alex Koford, in the core Terrapin band (Koford is the yellow node.) In contrast, Dead & Co and Wolf Bros are almost entirely a mixture of Boomers and Gen X.

Looking at this image, it’s clear that Phil Lesh & Friends and the scene around Terrapin Crossroads served (serves) as a—laboratory? workshop? conservatory?—for the musicians now carrying the songbook forward. One of our goals post-GDSA is to collect more data that might help us better understand the overlap between these three networks and the many ‘& Friends’ / Family bands that have formed over the last few decades, from Terrapin Flyer to Stu Allen & Mars Hotel, Grateful Shred, or Jerry’s Middle Finger. The very recently formed China Camp Family Band provides a clear example of the sort of cross-pollination we would expect to see; the lineup includes guitarist Garrett Deloian (from Jerry’s Middle Finger), keyboard player Scott Guberman (of Phil & Friends), bassist John-Paul McLean (from Melvin Seals & JGB), and drummer Jerry Saracini (from Stu Allen & Mars Hotel). In his announcement for the Heart of Town shows, Grahame Lesh employed the metaphor of a tree to describe this phenomenon:

My family has recently talked about the Grateful Dead’s legacy as a grand old tree, still growing after 60 years. Its roots are deep in the earth of America’s musical history. Its trunk is the original members of the band, and its branches and leaves are all the musical offshoots and musicians who were and continue to be inspired by the music of the Grateful Dead.

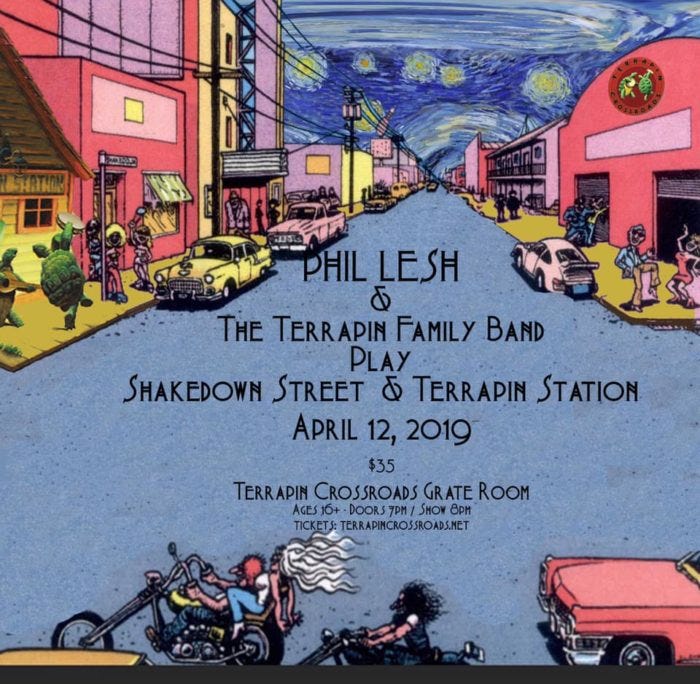

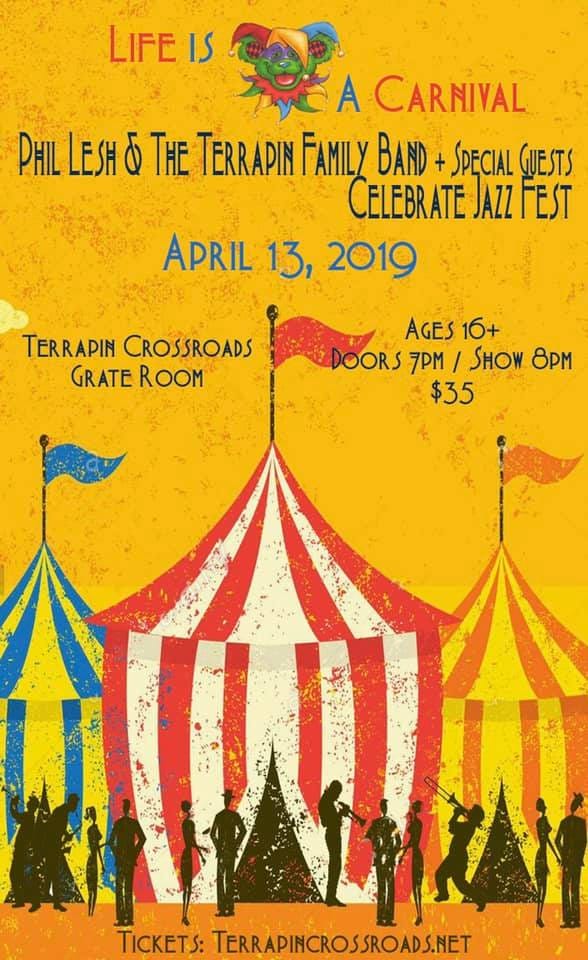

This sense of legacy, which requires generational diversity onstage, brought to mind its corollary, that is, the crowd. If it were possible to collect audience demographics our hunch is that they would look similar to the network visualizations above, with the exception of gender—we are fairly certain that more women show up in the crowd than onstage. Among Bay Area audiences, we have noticed a generational diversity that echoes the Lesh musician networks while also pointing towards something more difficult to get at, that is, the economics of the scene. Whereas stadium crowds tend towards the older and monied, smaller local venues and festivals are consistently intergenerational and include people who clearly didn’t drive their Tesla to the show. (Trust us, we’ve seen the bottoms of their feet.) We attempted to do some analysis of 2019 ticket prices to see what they might reveal about economic access. Dynamic pricing makes it almost impossible to collect consistent data but we dug up several Terrapin Crossroads fliers advertising $35 shows; $70 was the highest we saw. (And, always, this line: babes in arms free. In fact, if you are interested in catching the Truckee show in August, children under 5 do not need a ticket.)

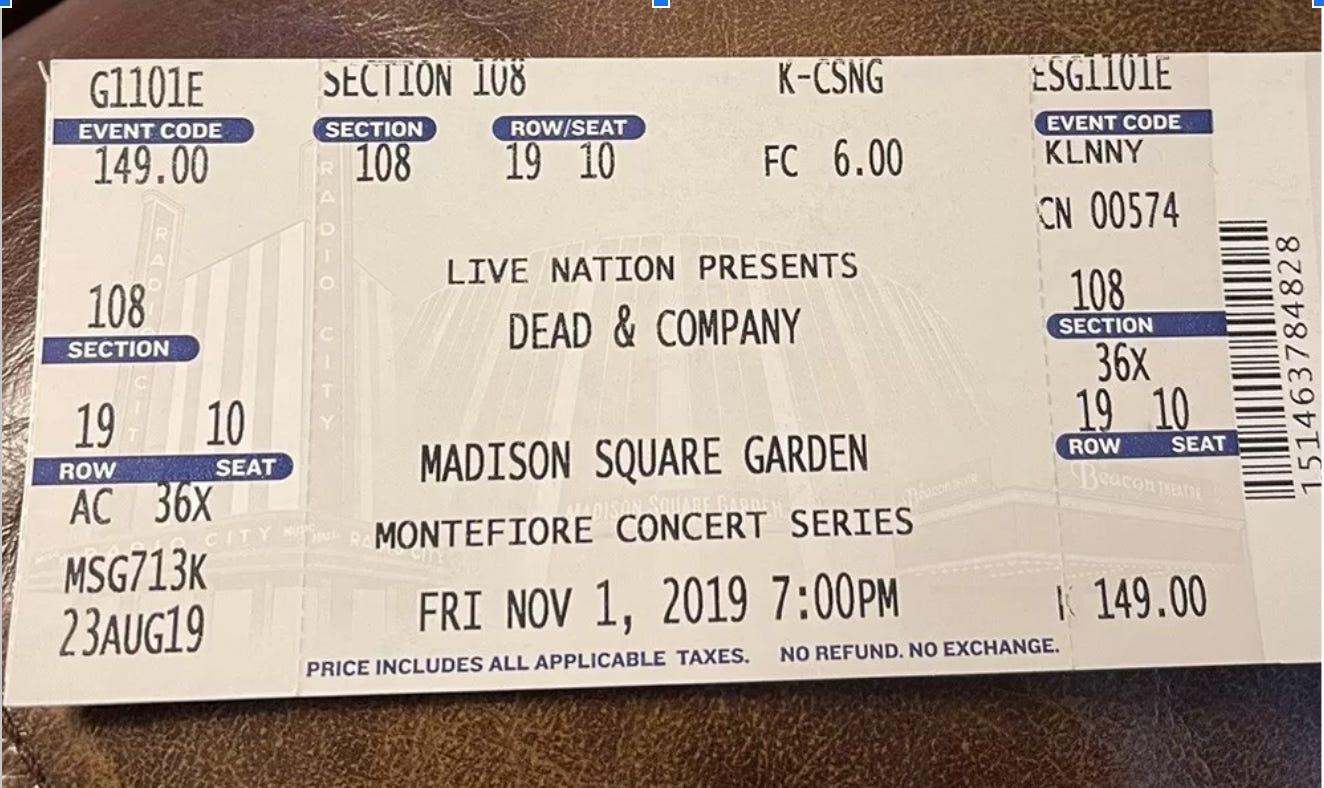

For Dead & Co, we found 2019 tickets for sale on ebay with a face value of $150, which doesn’t account for the resale market. In other words, differential access to shows as indexed by ticket cost is a phenomenon that defines the Dead & Co era (a decade that also overlaps neatly with the mainstreaming of psychedelics, but that’s a whole other post.) These differentials pale in comparison to the Sphere where tickets can run up to $600 for the floor or $2k for a ‘good’ seat. We don’t have details about the role finances played in the closure of Terrapin Crossroads, but think it’s safe to assume that the venue’s profit never came anywhere close to Dead & Co’s Sphere residency.

If this is all sounding very local scenes v the Sphere, well, yes and no. This Substack is called “Touch of Grey” after all; one of us wouldn’t have become a Deadhead if it weren’t for earlier cycles of commercial success. Since giving this talk, we’ve been thinking a lot about the scene that has sprung up around the edges of the financial maelstrom that is Dead & Co, catching the overflow from a crowd with disposable income and attention to burn. Something that big produces its own weather. While the economics of the Sphere raises enormous questions about labor, wages, and who can afford to be a working musician or vendor and who gets priced out, it’s also true that the most interesting things appear to happening outside the venue.

We’re thinking here of a band like Grateful Shred whose origin story includes getting busted for playing a free show outside a 2017 Dead & Co Hollywood Bowl show. Their about page is lightly critical of a phenomenon like the Sphere, or an approach such as DSO’s: Far from being a historical re-enactment, Grateful Shred’s laissez faire vibe infuses the band with a gentle spirit, warmth, and (dare we say it) authenticity.) Such claims to authenticity are supported by legacy connections; keyboard player Adam MacDougall played regularly with Phil & Friends is part of Circles Around the Sun, Alex Koford is a core member of the Terrapin Family Band, and Mikaela Davis has played with both Bob Weir & Wolf Bros and Phil & Friends. (Koford provides an interesting hinge as one of the youngest musicians in our dataset who went from working the door at Terrapin to…playing in the band.)

Another way to put this might be that the current metamorphosis of the Dead is the result of both hyper commodification & and the devotional spaces—musical, social— that Phil nurtured. Dead & Co’s national tours over the last decade have brought a huge number of people to the music for the first time, while Phil brought in new musicians playing in smaller, affordable venues. He mentored the collective thing. Often when we go to Dead adjacent shows in the Bay Area—which generally means a lineup connected one way or another to Phil—we see the same group of young people. They are not there with their mom and dad. The contemporary scene belongs to them as much as Winterland or Kaiser ever belonged to Clive or his generation. They are, in many ways, the reason it exists. They are constituted by it, and reproduce it through the social forms we recognize as central to the Dead, which have to do with caretaking of communal energy. They show up again and again. Sometimes they have a ticket; sometimes they sell jewelry outside. Other times set up an amp on the sidewalk, light a fire, and play an impromptu set for people waiting in line to get in.

So much of any scene consists of this, showing up again and again in order for the collective thing to happen, whether you can afford the cost of admission or you’re playing a free, unauthorized show outside the venue. The collective thing in this case requires—has always required—dancers.2 We can’t emphasize enough the centrality of dancers to the music nor the abandon that defines this dancing, which some have described as involving collective telepathy. This sort of dancer can’t get loose unless their friends are there to take care of them, the way they will take care of their friends in turn if someone takes too high a dose or encounters a creepy dude on the dance floor. When it’s working, our friends are everywhere, making space for the spinners and filling a water bottle at break, passing a joint or a ziplock bag of trail mix.

As we were searching for photographs from the 2024 Terrapin Roadshows at McNears Beach Park, we were struck by promotional images for this year’s Sphere residency. The poster evokes the sort of embodied, ecstatic experience that we understand as an integral part of the Dead. The dancers are clearly outside. (Clive initially thought it looked like it could be from Alpine Meadows, but during the Q&A at GDSA it was confirmed as a Jay Blakesberg photo from Laguna Seca, Monterey, May 1987.) In a screenshot from a video taken at the actual Sphere, people stand around on the floor, transfixed by the visuals, photographing the screen with their phones. We get it—we haven’t been there (yet) but have heard a lot about the overwhelmingly compelling visual experience, which might be more accurately understood in the vocabulary of theme park attractions. It even includes some spinners, onscreen at least.

At a recent Grateful Shred show in San Francisco packed with people recently back from the Sphere and looking for a fix (or so we assumed from their merch) the audience stood alarmingly still. While the Sphere has radically accelerated the popularity of the music, it has done so for a crowd compelled to sit, or to shuffle from side to side in front of their seats—a kind of de-skilling of the audience. Is it any wonder the most lively thing about such a venue goes on outside, for free, in bars or—like the Dead’s first show as the Warlocks—at pizza parlors? We can’t stop watching videos of Mason’s Children (another new ish band formed in the lot outside Dead & Co) from their current tour of bars and cafes where the audiences are small but getting down with the frenzy that metamorphosis sometimes requires.

If you stuck with us this far, thank you! We get to the songbook in our next post, with data about the songs most (and least) played by Dead & Co, Phil & Friends, and Bob Weir & Wolf Bros in 2019.

This was our first time using Gephi and we still have a lot to learn; as we collect more data and get better at using this tool we anticipate a greater complexity will emerge. Also, shoutout to Bricks AI spreadsheets without which we would not have been able to prep the data for use in Gephi.

In Get Shown the Light Michael Kaler discusses the crucial role dancers played in the emergence of the Dead: “It wasn’t just that dancing audiences provided a receptive environment for improvisational experimentation; in fact, the dancers and the band together formed the environment within which improvised and “wildly gyrating” magic could take place.” In the David Gans and Blair Jackson oral history volume This Is All A Dream We Dreamed, Garcia describes the “very real kind of communication going on between the dancers and musicians,” something Micky Hart calls a “giant breathing animal as one.” Hart sees band and audience sharing a similarly improvisational, yet anchored, structure: “You can have all these guys playing polyphonic parts, but we’re playing as one… the same is true of the audience. Everyone’s dancing differently, but they’re part of the same thing.” In his memoir Searching For the Sound, Phil’s understanding of the relationship between band and dancers is spiritual: “To make music for dancers like these is the rarest honor—to be coresponsible for what really is the dance of the cosmos.” He describes how “the experience of the group mind becomes much more intense” especially in large crowds where “the entire wildly dancing audience behaves like waves in the ocean: whole groups of dancers rising and falling, lifting their arms or spinning rapidly in synchronized movement, darting swiftly through the crowd or languidly undulating in place—manifesting the same sort of spontaneous consensus seen in flocks of birds, schools of fish, or clusters of galaxies.”