The light show during Deal epitomized Dead & Company’s last Saturday show in San Francisco: playing cards flipping through the air in spirals, tossed from some invisible dealer’s hand. Instead of looking down from above on the roiling crowd we found ourselves stuck inside it, our seats almost directly behind home plate. The intended audience for the lasers, in other words, like a money shot in reverse. It really did feel like getting hit in the face with dollar bills. These screen shots from the June 22 Citi Field show in Queens sort of give you a sense:

To reach the seats you passed through something called the club level, glassed in with wine bars like an airport concourse that went on and on. Galaxies away from the upper deck where we’d finally made our way the night before, as close as we could get to the outskirts of the organism, where we found our people spinning in circles. None of this had been clear to us when we purchased the club level tickets with S & S after they returned from being pressed against a cyclone fence for most of the Wrigley Field shows. Let’s get closer, we agreed, the sound will be better, having forgotten what stadiums were about. When we woke up Saturday morning and started texting about where to meet up, we realized we’d made a big mistake and tried to let them know: also shd say that we are unlikely to stay in our seats for very long bc it’s so hard to dance in those narrow rows, but we wanna hear the sound from that deck for sure! Lol Stephanie and Clive. We might have workshopped that text for clarity.

None of us could figure out why the tickets said restricted view. We were close enough to see what people on the floor were wearing, a parade of top hats, fairy wings, and steal your face maxi dresses. Everything was like that on Saturday. Way too close, but too far away to actually touch. We talked about the Friday night show. S had just missed “Casey Jones” again, but for good reason. They’d been on a plane the day before, the end of a romantic journey. The best part of the night was looking down the row at our friend during “They Love Each Other.” Lord, you can see it's true.

Otherwise that section was a mess, its money palpable in various forms: old, tech-derived, new, landed. Looky-loos. 30-something parents and their children in linen resort wear. When the families left at intermission it was just us and a bunch of dudes spilling beer and talking through the music about that time they saw Jerry, that time they were in the very front, that time before. We’ve developed a vocabulary for this kind of person, who always comes in a pair or group and seems remarkably uninterested in what’s going on in front of them. They push their way onto the floor to stand there, unmoving and ceaselessly talking or scrolling. It’s all or nothing with this type. Either they don’t see you as they stand on your toes or they leer, unfriendly.

We lasted until somewhere around “The Other One” into “Terrapin Station,” a few songs into the second set. Somewhere above us the upper deck existed. We only had to find it, while making sure we had proof of our tickets to get back onto the club level. When the door swung open the air outside felt fresh. All smoke, no vape. It got thicker as we climbed, crowded and frantic. The deck when we reached it more narrow somehow. It felt like turning down a street where we didn’t belong and anything might happen. We looked across the expanse at the other side of the stadium, its furthest edge. Utopia. How long would it take to get there? Too long. We’d miss a lot of the show, plus our friends were waiting a few levels down.

Except when we got back they were gone. We chalked it up to passion, an early departure for someplace more private, but S confessed a few weeks later that someone sneezed snot all over her. The story had the feeling of a final straw even though none of us wanted to be down on the section and its not cheap seats. None of us wanted to be down on the night in general, even though it felt off, with lots of hard stops and starts. It reminded Clive of of the 17-minute “Viola Lee Blues” at Fare Thee Well, when Bobby abruptly veered back into the melody just as things were getting weird and falling apart. It seemed like the band was fighting over who was in charge. We wanted to have shared a different kind of experience with S & S, more “They Love Each Other,” less the jarring shift into “Love Light” that followed. None of the final slog when it was just Clive and Stephanie and those dudes at the end of the night.

We kept dancing then like it was our job. A burned out skeleton crew looking everywhere except for the eyes of the men in front of us who finally gave up all pretense and turned around to stare, making comments about our clothes and bodies and other things we couldn’t quite make out or halfway did but didn’t want to. They were starting something with us, or trying to. The dancing actually was our job then. We would dance through it until they stopped or we did. As long as we kept dancing and didn’t meet their eyes we wouldn’t get into it with them, like, physically, a kind of magic spell we cast with our feet, dragging ourselves back and forth across the sticky concrete. We didn’t quite realize this is what we were doing until our encounter the next night with a crew of 90s tour kids grown up, our age now.

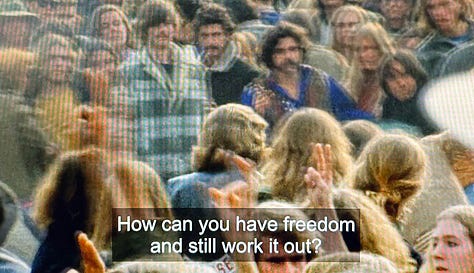

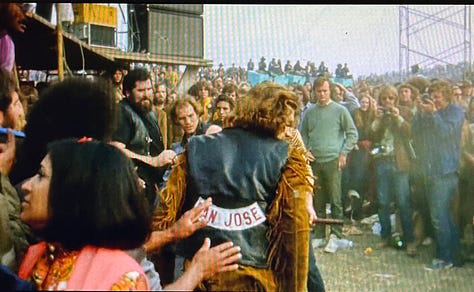

There’s this moment in the Long Strange Trip documentary when former county chair of the Wyoming Republican Party, co-founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and Grateful Dead lyricist John Perry Barlow—a complicated figure to be sure—talks about Jerry’s relationship to the Hell’s Angels:

In the voiceover from an interview that follows, Jerry reflects on freedom, a question as central to the Dead as change. The sequence begins with a pair of children running backstage, evoking a fraught and magical childhood that maybe resembled Clive’s, with freedom and danger in equal amounts. Sometimes because the adults were absent. Sometimes because they were present. Near the end of the montage a pair of cops talk to the Angels while a young Black person rides by on a bike. The camera zooms in on the bike rider’s expression, curious and wary. Whose freedom?

At one point a reporter asks Jerry who’s to blame for Altamont. No man, he responds, there isn’t any blame. Because who’re you gonna blame? You’d have to blame everybody, you know? We’re all human beings, we’re all on this planet together, and all the problems are all of ours. Not, some are mine and some are theirs. If there’s a war going on, I’m as responsible as anybody is. If somebody’s murdered, I’m responsible for that, too. If everybody is responsible, sometimes nobody is. A few beats later Barlow comments on the Jerry’s refusal to be the leader. Never mind that he was, and there was no way around it, and, you know, oftentimes bad things happened because he wasn’t willing to assert what was basically pretty obvious. We don’t want to spill more digital non ink on the possibilities and failures of the 60s or the losses of the 70s and 80s but for all Jerry’s elision of differences between, say, groups of humans on the planet, the questions still hit. The problem parts especially. If all the problems belong to all of us, how do we work it out?

We inadvertently launched this newsletter on October 9. It’s impossible to know what to do with or in culture or what culture is even for during a time of such deep despair and grief and as we witness ongoing genocide in Gaza. On the one hand this. On the other, we look towards the efforts of WAWOG. We return to this poem by Miguel James, translated by Guillermo Parra: If I write a Love poem it’s against the police / And if I sing the nakedness of bodies I sing against the police. If we write anything, however minor, we write for a ceasefire, even if as we type that it feels small and meaningless, verging on the kind of posturing that we hate—but we hate the occupation more (to quote @malefragility.)

When the music ended and the lights came up, 40,000 people tried to exit at once. We ran up the stairs onto the concourse, attempting to get in front of the wave but we’d missed our chance and edged along the side of the glass hallway towards a door that opened to reveal a packed stairwell. No way the person in front of us muttered, and together we returned to the club level, empty now except for a massive group of birds circling the field, gleaning whatever they could from empty wrappers and containers of half eaten food. We waited until the crowd thinned out. It was like that all the way onto the bridge, hours later, a mass of cars honking angrily as we tried to leave what we came for. Beep beep, motherfucker we cackled back and forth, beep beep.

That smell, one of us said, exhaust coming through the open windows and filling the car, that’s America: oil, gasoline, the grinding essence of this country. That’s the thing about the Grateful Dead. It’s all there. European folk music, bluegrass, country, jug bands, the blues, jazz, experimentalism at the edges of the academy; the music of settlers, of poor white people and enslaved Africans; everything created through or in spite of those histories. Violence and the beauty that survived it, music lost and taken and taken back up. The industry that benefited from asymmetrical encounters. The smell of exhaust. There’s no feeling of release at a Dead show without that smell, no “Ripple” without the strong sensation of something about to come apart at the seams. It’s right there in front of you. It is you. It’s one more Saturday night.