We have a fantasy that we passed each other at Shoreline in the summer of 1994. It could have happened. Maybe it did. In this flashback Clive is sitting on a blanket with friends, a couple who do not get the Dead and hate every minute of the music, the crowd, the whole scene. Are the couple actually his friends? Or more his wife’s friends? Something else? It’s complicated. Stephanie walks by, bewildered, wide-eyed, the person everyone walks up to at Greyhound stations. People are constantly talking at Stephanie. Her girlfriend often blocks them which she finds both helpful and a little demeaning. It’s the summer after her second year at a Presbyterian college after a lifetime spent in small schools attached to evangelical churches where, for reasons she will never understand, a young grad of Bob Jones University hired to teach Algebra I to a handful of 7th graders in a trailer behind the sanctuary took it upon himself to read out loud to the class once a month “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” This is before she knows anything about T.S. Eliot or Ezra Pound or the Southern Agrarians. That monthly reading of Prufrock in 7th grade is the highlight of her education to this point, setting her up to be a poet and ideal listener of Dark Star.

The friends, who Clive and Bonnie coaxed to the show, are the sort that Stephanie’s girlfriend would dancingly poke in the ribs during “Shakedown Street”: don’t tell me this town ain’t got no heart / you just gotta poke around. The friends are trying, they want to be open, but their boredom, verging on active dislike, makes it even harder for Clive to dance, the whole point of going to shows. He is very, very sober. Psychedelics in Recovery is not a thing yet, will not begin to be a thing until 2017. He is not that far on the other side of getting clean after the death of his dad, a sound engineer who worked in the music industry and once introduced him to the band, but that’s a different post. Although entheogens are woven through Bill W.’s story, founder of AA and the spin offs that followed, with rooms for overeaters and codependents and narcotics users and sex and love addicts and marijuana smokers and couples in recovery, it’s inconceivable to imagine sharing at a meeting (even a Wharf Rats meeting) that he engaged with LSD at a Dead show. This is still the 90s. There’s no #thankyouplantmedicine. Johns Hopkins has not launched the Center for Psychedelic and Consciousness Research. No studies have been conducted on the relationship between psilocybin and quitting cigarettes, something Clive and Stephanie are smoking a lot of. It covers up the trash smell, partly. Shoreline was built on top of a dump and caught fire a few times during its opening season until wells were installed to extract the seeping methane. If you stand in the wrong place at the wrong time, waves of the past wash over you. Decomposition.

We’ll try to quit smoking like 5,000 times and then, finally, we will. Cigarettes aren’t the only thing we’ll share over the years. We’re both the oldest kids in our families. Our dads died relatively young. We both spent time in rooms devoted to recovery, a peer support model that we will learn from until it no longer fits. Shortly after this flashback Stephanie will have a brief, fevered relationship with the MA in MDMA, around which so much stigma still circulates that here we are being coy about it, making sure it’s clear that her relationship with methamphetamine only lasted for a season. Clive’s went on longer, darker. Later we’ll think about how we made it through when a lot of people did not. People in our neighborhood. People we loved. We’ll take part in the movement to decriminalize psychedelics with all its contradictions and exceptionalism, and will agree 100% that a safer world would decriminalize all drugs, not just psychedelics, and yet still carry around some shame and ambivalence about our past.

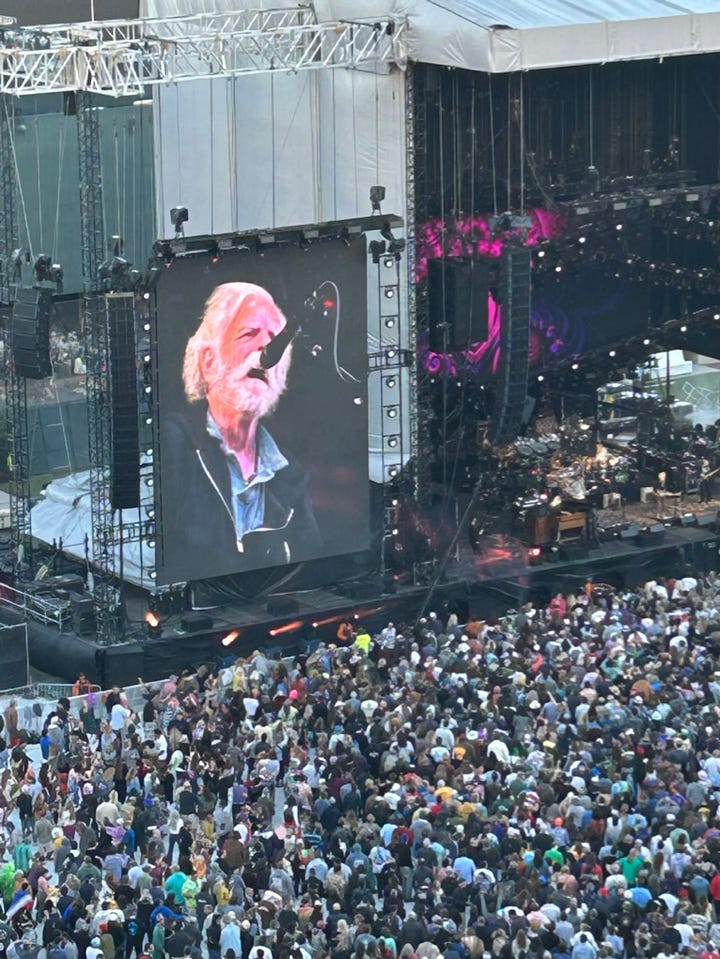

When we walk into Oracle Park together two decades later for the first night of Dead & Company’s final shows, it’s been a year since Clive’s younger brother died, someone who didn’t survive his relationship with stigmatized drugs. We’ve reached the point in our grieving process where we make his jokes to each other, often just a single word with a particular intonation. The longer jokes are deeply inappropriate, dumb, or both. And yet funny, really funny. Mark affectionately mocked most of the things we love in life and probably would have hated this show. On the other hand he might have been interested in the spectacle of it all. Unlike Shoreline, built for the Grateful Dead in the shape of a Steal Your Face, Oracle is the home of hot dogs and cotton candy, hard angles and stanchions. We promptly get behind them. The merch line snakes up three levels and Stephanie sends photos to Clive while he holds their spot. What should we get? We are babes in the woods, wide-eyed all over again, having lost the thread of stadium shows, what they are for and how they act on you. What even is a stadium? And why are we in the merch line, not shakedown street?

We haven’t been inside a stadium since Fare Thee Well in 2015, our first show after Jerry died in 1995 and the last time Bobby and Phil toured together. Since then we’ve slowly returned to the scene, Terrapin Crossroads before it closed and shows at the Frost, the Fillmore, the Warfield and the UC theater. This is our first time seeing Dead & Company. We couldn’t face John Mayer in Jerry’s spot until now, when it’s almost over. Almost immediately we realize that we should have been here all along, even as we try to get our bearings in this crowd which leans towards that particular brand of Dead merch disguised as Giants merch, or the ubiquitous Morning Dew t-shirts hidden inside the Mountain Dew logo. We pass endless examples of both when we finally make it to the front of the line, get our sweatshirt, and head to the very upper deck where we somehow wind up in yet another merch line while trying to get a beer.

There are so many parents with kids up there, the parents around our age ish, their kids the age of kids Stephanie taught in college poetry workshops over the years or the age of grown up kids who Clive taught when they were little. We see a whole family from the Cal Shakes summer conservatory program in the parking garage, everyone in matching tie dye. There are so many different kinds of parents: weirdos in blanket onesies, dudes in crew cuts and fleece, someone who drove down from Portland and wants to talk about all the shows he saw in the 80s while his goth daughter sways nearby. When we reach our seats almost all the way at the very top of the stadium, we run our teeth lightly across a chocolate truffle and look at each other in surprise when Bobby launches into “Not Fadeaway,” a song to end the night, not begin it, when you’ve been through something together and want it to never stop, when everyone sings along and claps in unison, our love is real, not fade away, not fade away. Clive leans over and whispers, they’re going to come back to this on Sunday night.

Sunday: the last show Bob Weir will play with this band but not the end of the music. Everybody is saying so—the Dead & Co Touring Family Facebook Group, the New York Times, the chat on livestream shows. Something will come next. The music goes on in the hands of the players who hold it. We don’t have tickets yet for Sunday and this is the point when we realize we need to get some. Someone told us once to never miss a Sunday show. We’re coming back on Saturday with friends; it’s been a long complicated road of purchasing tickets in one tier and reselling them in another and who knows how expensive Sunday will be now. Should we spring for the floor, where we could really dance? Think about yourself twenty years thirty years ago, Stephanie says, if you had the money in the bank, wouldn’t you get a ticket for the final Sunday of the final tour?

We do our best through the beginning of the first set, shuffling from side to side in front of our seats through “Shakedown Street” into “Cold Rain and Snow” followed by “Ramble on Rose” and “Brown Eyed Women.” We smile at the people next to us when we accidentally knock into them, then again a few minutes later. Very quickly it gets vertiginous, a person could lose their place up there and topple forward, the chocolate coming up stronger than expected. We keep doing this, just barely running our teeth over the truffle and getting surprised. We clutch the railing on our way down to the deck where the stadium curves, where we saw a handful of people in the distance before the show started, on the edge of the world where the view of the stage is not just obstructed but non-existent. A guy spinning out there in some kind of triangular hat. That’s where we’re headed.

We find a spot near an entrance with a handful of people trickling in and out. A 7-year old rolls a blinking hula hoop down the hallway and back up again. It’s so much better down here, flat with room to move. A staff member posted up by the ramp says he’s been talking to a kid wearing a steal your face who didn’t even know what it was. He had to explain it! He wants to commiserate about the youth but we are moving now and can’t talk, we shout GOOD WORK MY FRIEND! and beam at him with the laser eyes of our attention, the way Stephanie’s been witnessing people all night. That’s her special gift, she realizes, to see people and witness them, whatever makes them so particular.

At intermission we talk to a giggling dad we saw earlier on the concourse, posing for a photo with his elbow propped on a pile of plastic trash bags about to fall from an overfull cart. His son chortles when we mention the photograph, oh yeah, Uncle T, that’s Uncle Trash if you don’t know. We tell the dad you’re a big dumb dumb and everyone leans over laughing harder. The kid is wearing an Obama 2012 election t-shirt and what feels like performative American flag pants that we can’t quite figure out, stripes down one leg and stars over his crotch. He’s a joker, goofing with his dad for his girlfriend’s benefit, so chaste they appear to be siblings until the second set starts and his dad goes to get a drink. Something passes over the son briefly, a pause, arms wrapped around his girlfriend. Then he’s joking again, the way we perform for our parents when they’re not even there.

Like a steel locomotive we sing along nearby, rolling down the track, he’s gone, he’s gone, nothing’s gonna bring him back. We move closer, leaning in, our dads in mind. Gone so long now we cannot always conjure their faces, not exactly. Mark’s face is still fresh, the sound of his voice, okay, rising on the kay, laughing. And then we are in it, what the ceremony is for, the curve of cement at our back, the vast and velvety crowd below, lit up against the sky and the water. “He’s Gone,” the song that has gotten us through so many deaths before, the song we know we will turn to after deaths still to come.

The sound is not perfect but very loud and coming through in waves, moving our bodies through Space into “Standing on the Moon.” We are, while colors from the stage move across the crowd below, a moving body. A lovely view of heaven, but I’d rather be with you. We move with it, the dad of the kid with the hula hoop, the dad of the goth teenager, Uncle T, the guy in the triangular hat, spinning where the stadium comes to an end, just before the very last exit and beyond that the shuttered food stands.

“US Blues” comes up almost underneath us as the set ends, working our hips the way this entire night has been, a little much. Stronger than expected. We won’t have the language for this experience until a few nights later. We hear as if for the first time the truth of the song: summertime done come and gone, my oh my. Foretold in 1974, now it has come to pass, summer as we knew it: gone, gone, completely gone. In its place whatever fire and smoke, whatever seasons in their wobbling rotation are coming next. You can call that the US Blues. The trash heaped so high, about to fall over. We fly past it during the encore, “Knocking on Heaven’s Door” but we’ve done our work for tonight and head down the concourse half running, half skipping, getting out before the stadium grinds back open, before it’s time to return tomorrow.