Let us again pretend that life is a solid substance, shaped like a globe, which we turn about in our fingers. - Virginia Woolf

Woolf’s sentence has been lodged in my mind since we returned from the Grateful Dead Studies Association’s 5th annual meeting, part of the Popular Culture Association’s national conference. This was actually the group’s 27th meeting since their inception in 1998 as an area of the Southwest Popular/American Culture Association. (It’s complicated.)

Life, in this case—to rewrite Woolf—was the Dead: a phenomenon far from fixed and spinning from one disciplinary horizon to the next. Over the course of four days and 15 back-to-back panels in the same room with most people attending for the duration, we heard political scientist Paul Collins discuss legal consciousness depicted in lyrics (82.9% against the law); musician Alfredo Guerrieri analyze Phil Lesh’s use of counterpoint; and curator Susie Silbert trace the origins of glass pipes from the 90s lot to global mass-production and, more recently, artisanal collector's items. That’s just the beginning. Brian Felix gave a talk entirely devoted to the history of the Hammond organ, the sound of which as played by Brent Mydland or Melvin Seals makes some of us feel like we’ve been shot into outer space or heaven. Literary scholar friends: the only formal analogue I can come up with is to imagine a single ACLA seminar going strong for almost 30 years.

Poetry scenes are the other obvious analogue. When I saw Clive’s welcome packet with “Independent Scholar” listed where an institutional affiliation would otherwise appear, I thought immediately of the many hours Kevin Killian spent at the Bancroft working with Jack Spicer’s archives. Peter Gizzi describes how Kevin “transformed the stodgy hush hush of the Bancroft into a happy hour! He made magic and fun out of his life.” I wish I could ask Kevin what he might have known about lesser known Dead lyricist and poet Robert M. Petersen (not to be confused with Robert Peterson) who gave us “Unbroken Chain.” I learned that he was friends with Lew Welch during the Q&A following papers by Nathaniel Racine, Christopher Coffman, and Nicholas Meriwether situating Petersen’s work in relation to environmental writing and the rest of the Dead’s catalog. Books by Charles Olson, Gregory Corso, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Gary Snyder and others sat on his shelves but Petersen does not seem to have been meaningfully embedded in the that social world.

I went around all week telling people how much the conference felt like being in my 20s and 30s, wandering around in clumps of poets at the Boston Poetry Marathon (not a conference, but adjacent in that way of being together, listening, in a room for days) eating and drinking and endlessly talking, wandering around LA at the CalArts noulipo conference, or the deeply messy 2010 Rethinking Poetics conference.

These worlds aren’t disconnected; serendipitous connections abounded. Curator Susie Silbert is friends with poet Joey Yearous-Algozin. Burroughs scholar Davis Schneiderman, whose talk on AI and the Sphere formed one turn of the wheel in which we alternately decided from one day to the next that we must / must never go there, co-directed &Now. We talked about the final iteration of that conference in 2015. I had almost forgotten giving a talk on the Anti-Surveillance Feminist Hair & Makeup Party, a project that feels quaint ten years later. (Going around doing that makeup at AWP is maybe the last time a conference felt almost ecstatic.)

In other words, it feels a lot like we just experienced our first show, if a conference could be a show, held this year in a city at the heart of the Dead’s musical DNA—though as Andrew McGaan pointed out in his talk on their 1970 New Orleans arrest, the band rarely played there in the years that followed despite it being an obvious tour stop. The affinities between place and study went beyond the historical or strictly musical. After the conference ended we found ourselves at New Orlean’s annual gay easter parade. The city’s orientation to collective performance feels deeply related to a quality Jerry described in 1967, one that defined the Dead’s emergence: “There’s a very real kind of communication going on between the dancers and the musicians. If you’re a little stoned, you’re less into yourself, less into demonstrating your ability, you’re less into your own thing, and more into the total thing.”

For those of us in search of intellectual conversations more into the total thing who can find ourselves disappointed by academic contexts shaped by the anxieties of demonstrating your ability, GDSA’s annual meeting felt like stumbling into a room of scholars and practitioners living the literal dream. Part of this has to do with the value placed on kindness, an ethos woven through Dead lyrics and attendant culture, cultivated too by Meriwether, GDSA’s Executive Director. (I notice here that I feel compelled to underscore the rigor of scholarship being produced, as if kindness were a solvent causing rigor to drop out.)

In this 2024 interview, Meriwether discusses the work of making the Dead an acceptable area of academic study. He was the founding Grateful Dead archivist at UC Santa Cruz, where he supported a huge number of young scholars—work that continues through the GDSA and in his role as editor of Duke’s new Grateful Dead Series. Meriwether’s presentation on Alan Trist (director of Ice Nine, the Dead’s publishing arm, among other roles) quoted Jerry describing Trist as “some kind of cosmic diplomat” and I can’t help but think that this describes Meriwether, too.

I wasn’t the only mid-career academic enlivened by the GDSA. The generational rings of the room included those who’ve attended a decade or longer and people returning for a second or third time. Meriwether’s efforts are gaining traction. I’m guessing this could feel complicated for those who have been there from the beginning, similar to Dead & Co’s new fanbase—a vexed subject for those who held it down during the many decades it remained deeply uncool to be a Deadhead. A few days after we got home I presented a version of our talk to a group of digital humanities scholars and computational social scientists only to realize about 5 minutes in that I hadn’t code switched anywhere close to enough. Imagine what it must have required, institutionally, for sociologist Rebecca Adams to take 2 classes on tour in 1989 (!) Jesse Jarnow, whose presence in the room felt like an archive come to life, or, as he described himself, its librarian, hosted this episode about the GDSA where Adams discusses that experience.

Which brings me to Susan Balter-Reitz’s keynote on commodification of the Dead’s audience. I can’t stop thinking about the Meaghan Fabulous images from her slides and feeling a little dumb that prior to the conference, when the algorithm fed me Dead-themed luxury wear, I assumed incorrectly that Fabulous was a shakedown vendor who’d hit big.

Recent ads feature glossy people at the Sphere, a location about which the room held wildly divergent opinions and that Balter-Reitz, a communications scholar, wisely set aside to analyze instead the recent corporate capture of Deadheads as consumers of popular themed sporting events and fashions both high end and fast. Building on Dallas Smythe and the idea of ‘parallel tracks’ in which the dialectical absorption of counter cultures allows groups to exist simultaneously with their commodified versions, her talk suggested, I think, that some social practices remain indigestible.

I’ve been turning this around in my mind ever since, like a globe. It’s impossible to separate the Sphere’s business model a market that can afford a $500 GD Yacht Blanket coat, any more than I can separate my midlife return to the music from the decade during which I found my way back, years defined by the rise (again) of stadium shows, officially licensed Old Navy t-shirts, and a resurgence of psychedelic clinical trials. It didn’t feel like I was part of a larger cultural turn, but does it ever? I remember it was news to me when, after a 2019 reading where I sheepishly alerted the audience to Dead content in a newly published long poem, someone around my age made a point of letting me know that people didn’t hate the Dead anymore.

In the Q&A after Balter-Reitz’s talk, Merriwether noticed that anxieties about commodification killing the phenomenon have been present from the beginning even if the opposite has often been true. Annabelle Walsh’s far-ranging account of Dead fashion included an exemplary sartorial expression of this: the ubiquitous 1980s era “Morning Dew” t-shirt, which surged in popularity post “Touch of Grey,” newly popular all over again. Vintage originals can be found on Ebay; contemporary iterations range from the pre-distressed to custom made. The gesture—hiding inside a commercial logo—translates we are everywhere, a phrase that launched a hundred stickers and which “used to suggest infiltration and serendipity” as Nick Paumgarten writes, but now “implies saturation and perhaps even a kind of cultural fatigue.”

Maybe you are wondering why at this late date in history I am belaboring something so banal as the commodification of a band and its accompanying subculture of freaks-cum-customers. In the last post on his substack in 2021, Joshua Clover wrote “I think Taylor Swift is truly great but it would make more sense if she were named Tesla.” Joshua, who left this world last week, something I have not wanted to type despite circling the fact of it in these notes, and who wrote at brilliant velocity about loving music (all while claiming to be a slow writer), toured, as it turns out. For a time, briefly, when young. It would have been the early 80s. Either I never knew this or I did but it didn’t mean as much to me when I learned it as it does now, so I forgot. I might have intuited the outlines of a shared experience from the tenderness he brings to Don Henley’s line about a Deadhead sticker on a Cadillac in that last substack post, which is about knowing something is over even as you are writing about it: “I think this is the stuff you have to know to write a perfect song, or to write the perfect song that is “Boys of Summer,” to write the end of your own story without even dying.”

There are all sorts of arguments I can imagine myself losing had we ever talked about it. Some would have been specific to Joshua and some not, like my objection to the commonly held idea that the Dead ended long ago, in 1974, or 1987, but certainly by 1995, the remnants held in memory now or the vast corpus of tape recordings made by audience members and sound engineers, living on as songs played by cover bands and vampiric cartoons of Haight Ashbury on a 240 foot tall screen with 64,000 LED tiles.

And yet. In her talk on the Dead as an emergent phenomenon, Jayne Stone wondered how we might understand the contemporary proliferation of cover bands. It’s a good question, especially given that the Dead started out as one. Can something emerge more than once? Continue emerging? Come back to life over and over after commodification to the point of expiration? As a metabolic register of the present, one might understand this proliferation as Billy Strings did when he stopped playing from the songbook: “too many pigs on the teet.” Alternately, the fact that one can attend three or four Dead-related shows in any given week in many US cities might reflect the algorithmic splintering of our time (the Dead as yacht rock, as drag, as African, as brass band, as all-female.) Or it might be that the Dead continues to offer a particular experience of the kind that Jarnow discusses on that same podcast episode, transformational and ecstatic, capable of unpredictability both internal and external within a given structure, or form:

JESSE: In our last episode, “Dead Freaks Unite,” Steve Silberman talked about how the second half of Dead performances were the musical embodiment of a psychedelic journey, and Rebecca Adams shared data about how this structure leant itself to deep personal realization.

ADAM BROWN: That structure provides for something like a meditation, where you kind of accept whatever happens within those two sets, and the different points of that journey without really trying to change anything; this is the framework for which we are okay with whatever directions it takes. Certainly with impermanence, I think we see this again and again, both in Barlow and Hunter’s writing — we know that if there's one thing we can count on, it is change.

Our talk in New Orleans ended with Octavia Butler’s iconic sentences about change, sentences that run parallel to Woolf’s, who also understood what her narrator could not accept, that life is far from solid: All that you touch you change. All that you change changes you. The only lasting truth is change. God is change.

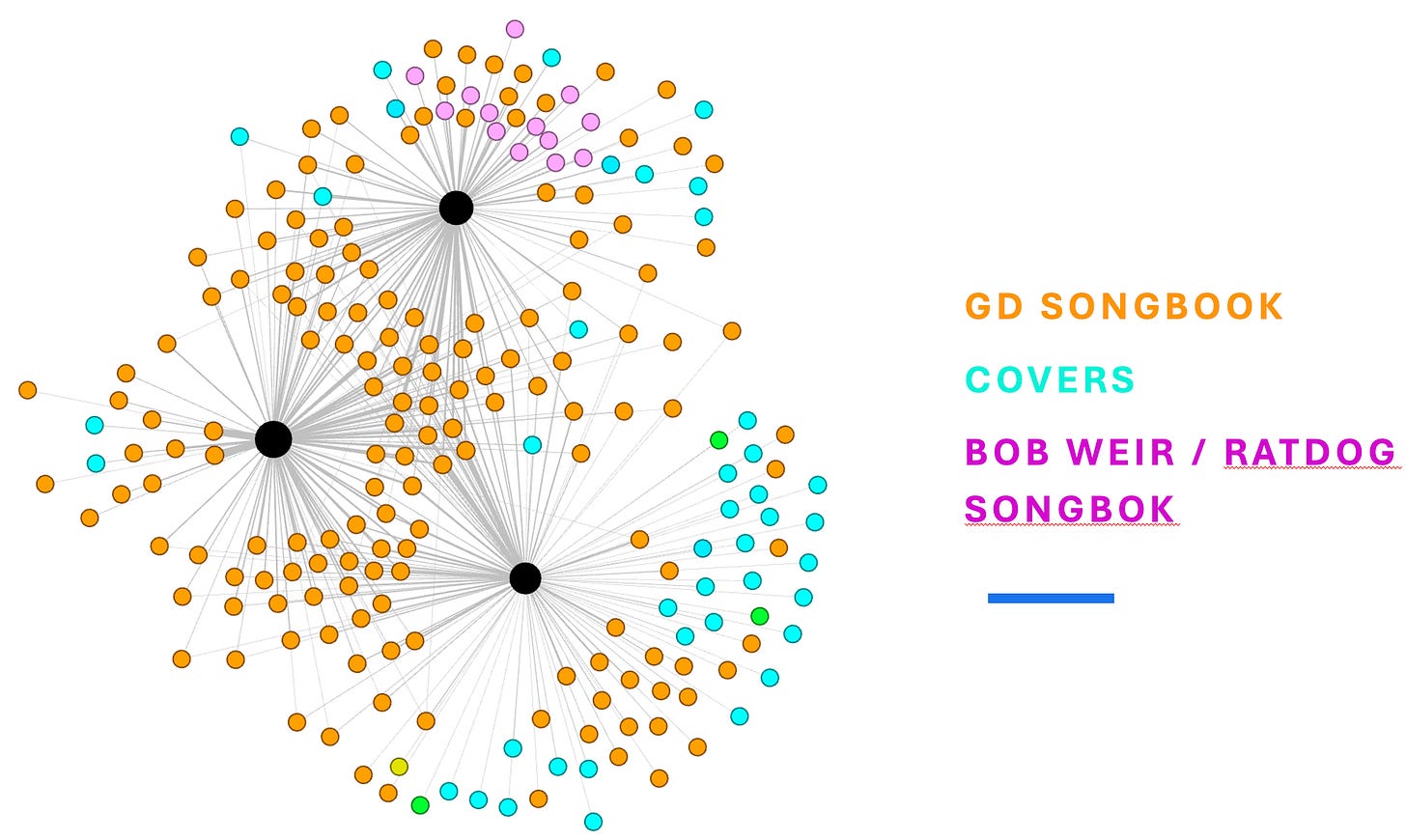

Here’s a data visualization of what I mean. This is from part of our analysis focused on Phil Lesh & Friends in comparison to Dead & Company and Bob Weir & Wolf Bros. The image below depicts the unique songs each band played in 2019 (we also looked at diversity of personnel, which is astonishing—in the single year we gathered data for, Phil played with 53 unique musicians.) Phil & Friends is the black circle in the lower righthand corner, Dead & Co is to the left, and Wolf Bros are at the top. We defined covers as anything the Dead never played when Jerry was alive. You can see that the music as Phil played it was very much alive, and always changing. (The orange dots between all three bands might represent something like the contemporary canon.)

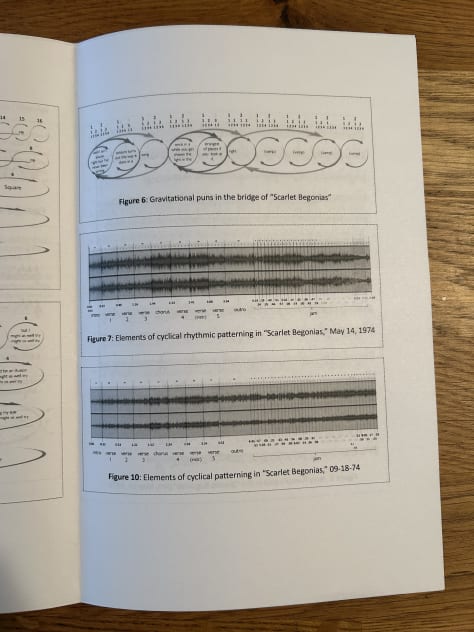

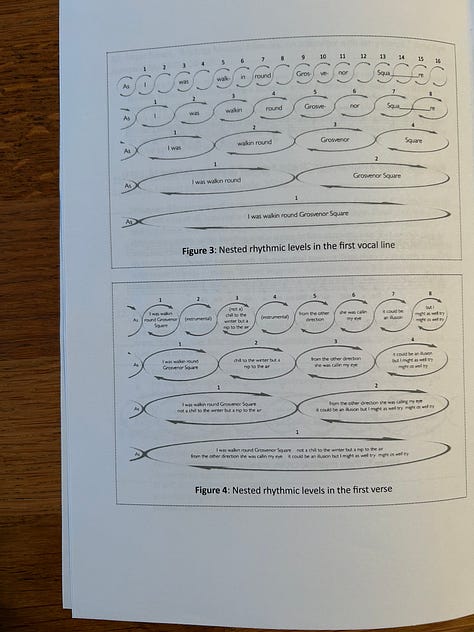

Our provocation—that the Dead isn’t over—isn’t our idea. It’s in the air, especially now. But I wouldn’t have thought it without Phil and the scene he cultivated around Terrapin, Phil whose death I hadn’t really incorporated until New Orleans, maybe not until Graeme Boone started crying as he played the 1969 Live/Dead “Dark Star” in that hotel conference room, the unhinged arrival of something holy. We heard so many stories from the musicologists about Phil, who did not even know how to play bass when Jerry asked him to be in the band and yet who came to be known as a perfectionist easily frustrated with his bandmates; a complicated person to be sure. Brian Felix, whose homework for the room was to listen to these two episodes & read this book told a story about someone approaching Phil to say how much they admired him as a bassist. When Phil asked what they’d learned from listening to him, they responded “absolutely nothing.” The right answer, as it turned out. That said I did actually learn a lot from the musicologists. When we heard a street musician playing “Deal” I thought it was “Keep Your Day Job,” probably because Chad Jenkins demonstrated how the latter is a retread of the former.

I used to think that growing up in the church prepared me to be a poet. Now I think that being a poet prepared me to be a Deadhead, always good at losing myself in the crowd but finally also the sort who will not forget anytime soon that “Unbroken Chain” was first played live on 3/19/1995. It’s not a great version, but the sound of the crowd as they register what’s happening is one of the more moving things I’ve experienced in this lifetime.

You don’t know the function of a diminished chord until it’s resolved—something else Jenkins said. It rhymes with these disconnected fragments from my notebook, the marks of a thread that ran through conversations all week about shapes you can’t see while you are inside them.

Form follows feeling—>Barg on Alan

Content follows form—>Hunter

When someone asked after the conference afterparty about my first show, I flubbed the answer as usual. It goes something like: black and rose bikini top, lightning storm, food wrapped in foil, a long line of headlights. The ground seemed to be covered in hay or dead grass. Wandering through that, lost. Anxiety and release. I know the names of these places and the years too but I can never keep them connected. Las Vegas, Shoreline, Portland Meadows. Apparently my last 1995 show looked like this. Chuck Berry opened. I wish I had told Joshua that. I wish I could.