not fadeaway: dos and don'ts

on multiple endings, the sphere, the last Sunday Dead & Co show in San Francisco last summer, and lessons from 90s tour kids

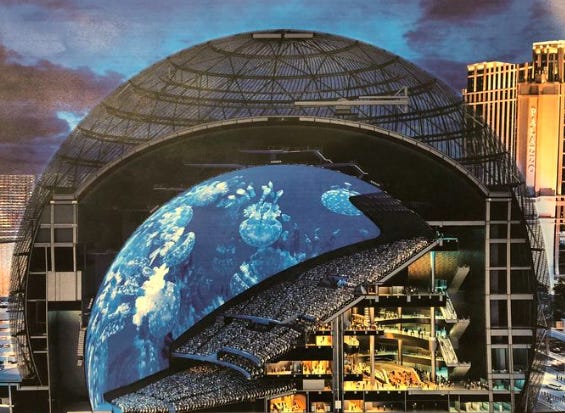

If you’ve been following along (hi!) you’ll know this is the last in a series of posts about the last three Dead & Company shows in San Francisco last summer, the experience that inspired us to start this substack. When the Sphere shows were announced last week we felt a little silly about having fallen into the idea of a final tour, but prepared to queue up with everybody else and pay way too much money. Then we figured out what the Sphere is and went down the reddit forums. There are a lot of obvious things to say about it. Jerry always dreamed about playing in one place, about the audience coming to the band instead of the other way around. As Bill Kreutzmann put it recently, “the Dead were always about transformative experiences” so it makes sense “that part of the tradition continues” with “residence in a transformative venue.” The sound is apparently incredible, with speakers in every seat and 4D effects. Maybe that’s what VR is? IMAX gone Disney?

There is a lot of debate: about the overhang, how to deal with vertigo, 200 v 300 v 400 level seats, whether or not ushers will enforce the seating policy, or police will enforce Las Vegas’s (very restrictive) vending ordinances, or if it’s safe to get high in a VR space (“Oteil said in an interview that he doesn’t think anyone will need psychedelics because it’s soo immersive.”) Most crucially, for us at least, the Sphere was designed for sitting down, like a ride. As @NoSpirit57 wrote: “The spinners will be miserable. There's nowhere to move like that and the hallways are soundproof with a weird ambient binary beat like hum. So you can't hear the band at all in the hallways. Can't hear a note.” We guess the Sphere heralds a new future for entertainment about which we would sound like dodos if we said much more, but we’ll be sitting this one out.

We’ve been reading Fare Thee Well finally, a gossipy account of the Dead after Jerry’s death and tbh a painful, if illuminating, reading experience to be taken with many grains of salt. It’s hard not to understand the Sphere residency dates as an expression of the lower level bewilderment and upper level disdain that some band members may have shared for a certain kind of Deadhead, per Joel Selvin’s account. If that’s even true, it wasn’t always. The band used to put speakers in the hallway for spinners and people like us, dancers who need room to move. How many nights did Clive spend in the halls of the Kaiser auditorium?

Stephanie would give anything to go back in time for one of the Lunar New Year / Mardis Gras / Valentine’s Day runs, to experience the floats and balloons and streamers, a circus parade which could not have happened without the audience, specifically not without their bodies. At 3 am, breakfast carts rolled through to deliver a small cup of orange juice and a morning bun for everyone. As long as we are going back in time, why not the mind blowing shows with Etta James and Tower of Power which one of us got to experience firsthand, something the other one will always be envious of?

Whether you think, as Fare Thee Well suggests, that Phil Lesh was canny in his cultivation of the Deadhead scene after Jerry died when everyone in the band was scrambling to maintain their income, or that Lesh was actually committed to forms of life and participation so ardent that it’s embarrassing to consider their role as financial levers (or, more likely, something somewhere in between) we still believe there’s no Dead without the audience. This is about that, a story we are glad to finally finish telling as we prepare to usher in the Year of the Dragon. We’re still thinking about that Sunday night show, still working with its lessons which you might say we took as dogma and are working backwards now to integrate as something more subtle and adaptable, a kind of gift, something we might pass on.

By Sunday night we remembered what to do and made a plan: get the cheapest seats we could find, arrive early, go to the upper deck, find a space to dance, hold onto it. Eat some protein mid-afternoon. We brought tourmaline for protection. Clive wore a small amulet pinned on his fanny pack and new Hokas from Sports Basement. He needed something bright and bouncy, like us, like the woven lavender journey shawl that Alli got on buy nothing. Stephanie put on the aggressive rainbow Gucci logo windbreaker from the last clothing swap with poets. She’d laughed when Violet pulled it out from under a heap of sweaty textiles at the end of the day. Ugly, garish, possibly beautiful. The night before, when we arrived at Oracle and Sophia saw the windbreaker she asked incredulously, is that Gucci? Yes, but we’d almost forgotten. Away from poets and our clothing swaps the jacket’s heavily ironized decadence reverted to its factory settings. But the windbreaker was a rainbow, and easy to track in a crowd.

We flew through the entrance. Not tonight, merch line. At the very top of the stadium, wind ran across our bodies and the sea stretched past condos beyond the park. We stretched against the wall, a modified natarajasana. We knocked on the gates of life. We did runner’s lunges. When someone nearby pulled up her long skirt for malasana we squatted down with her.

The crew arrived just after Clive left to go to the bathroom. They mystified us at first with their heterogeneous looks. Someone in a simple sundress. Someone with long reddish pink hair wore an outrageous custom made outfit, stealie bell bottoms and a matching vest. The one man in the group asked if they could join us and Stephanie hesitated briefly, there’s another person with me, but sure. He was smiling with big blue eyes that reminded us of Dom from Looking. They’d seen us across the way he said, we saw you stretching and came over. Like the person doing low squats in a long skirt, they had a story about being on the floor the night before and how terrible it was down there. Some kind of weird vinyl covering made it hard to dance. The man was talking a lot, setting the terms. We come here to dance, that’s what we do, we don’t come here to talk. He asked if many people walked through this way, if the security guards stayed all night. He turned to the rest of the group: I said we wouldn’t talk so you better not talk! Laughing, remember the time that someone let us into the empty private box? That time in Vegas? He told the group to give us plenty of space, to let us dance.

A younger man, out of it, drunk or something else, wandered through, dazzled by the woman in a custom set and reddish pink hair: I love your outfit!! She said she got it from The Good Witch, they make bathing suits, rash guards, the whole thing. She sorted through a container of pills with one of the others, a nurse, no that one’s a muscle relaxant, it’ll make you sleep. We’d already taken our anti-inflammatories before we left the house. The woman sorting the container said she was 50 but felt like 70. Her back was out. Maybe it was a slipped disc. Stephanie lit up. I’m 50 too! Or about to be. So was the rest of the group. Someone else turned 50 in January. Someone had just turned 50 last October. A small argument broke out over the pros and cons of cortisone shots. I’ll stretch you out later, the man said in a low voice to the woman with the long hair.

The nurse asked if we wanted a drop from the bottle moving through the group. We remembered why people bring liquid to shows: it’s easier to share. We already took our medicine, we declined. Then we’ll all be in the same place soon. The nurse lived in Mammoth. Someone else lived in Chico, she moved there after the second time Jerry got sick in 1992, the same year Stephanie graduated from high school. After she moved to Chico she just stayed. She told Stephanie about her new job as an art teacher, her new boyfriend, someone who ran marathons. And here I am with my mom bod she laughed. Her kids were older now, 18 and 21. The nurse said it was so much easier to tour than it used to be, you could fly instead of driving. We said it must be expensive and she gave us a look, I mean, I took out a home equity line of credit. We talked about people in Chico displaced by the Paradise fire. Dom worked at a hotel. Another pointed look. I have a real job. He’d taken two weeks of vacation to catch the last leg of the tour.

We realized then how we must have appeared with Clive’s brand news Hokas and Stephanie’s Gucci windbreaker. The nurse wore dirty Asics and baggy pants with a long dress on top, a tour uniform circa the 90s. Stephanie had blurted out that Clive ran a space in the hills, beyond the tunnel, ALO was playing later this summer, they should come. The crew murmured sure disinterestedly. Maybe we looked like tech people, or people who left early and didn’t dance, who drank cocktails and bounced on their heels and nodded their heads, or who didn’t share their expensive drugs, people who either held back or got way too high and shouted COME ON during “Space” while their girlfriends smiled and apologized.

When Stephanie told them she taught writing, something lifted. The music started and we kept talking until the younger person in long skirts came over with a finger over her lips, please don’t talk while the music’s playing. And she was right. It was nice to be shushed for once instead of doing the shushing. We moved together without language then. The aisle, a deck, a starship, a block of energy. When the younger man returned with his shirt off and started dancing closely behind the woman in a sundress she turned it into a kind of four step. Dom looked over are you ok? She rolled her eyes, it’s fine. After he returned for the second or third time and she told him to stop the rest of us made our way between them, still dancing. When we blocked him he tried to move in on another body in a dress, so we blocked him again until he stopped trying.

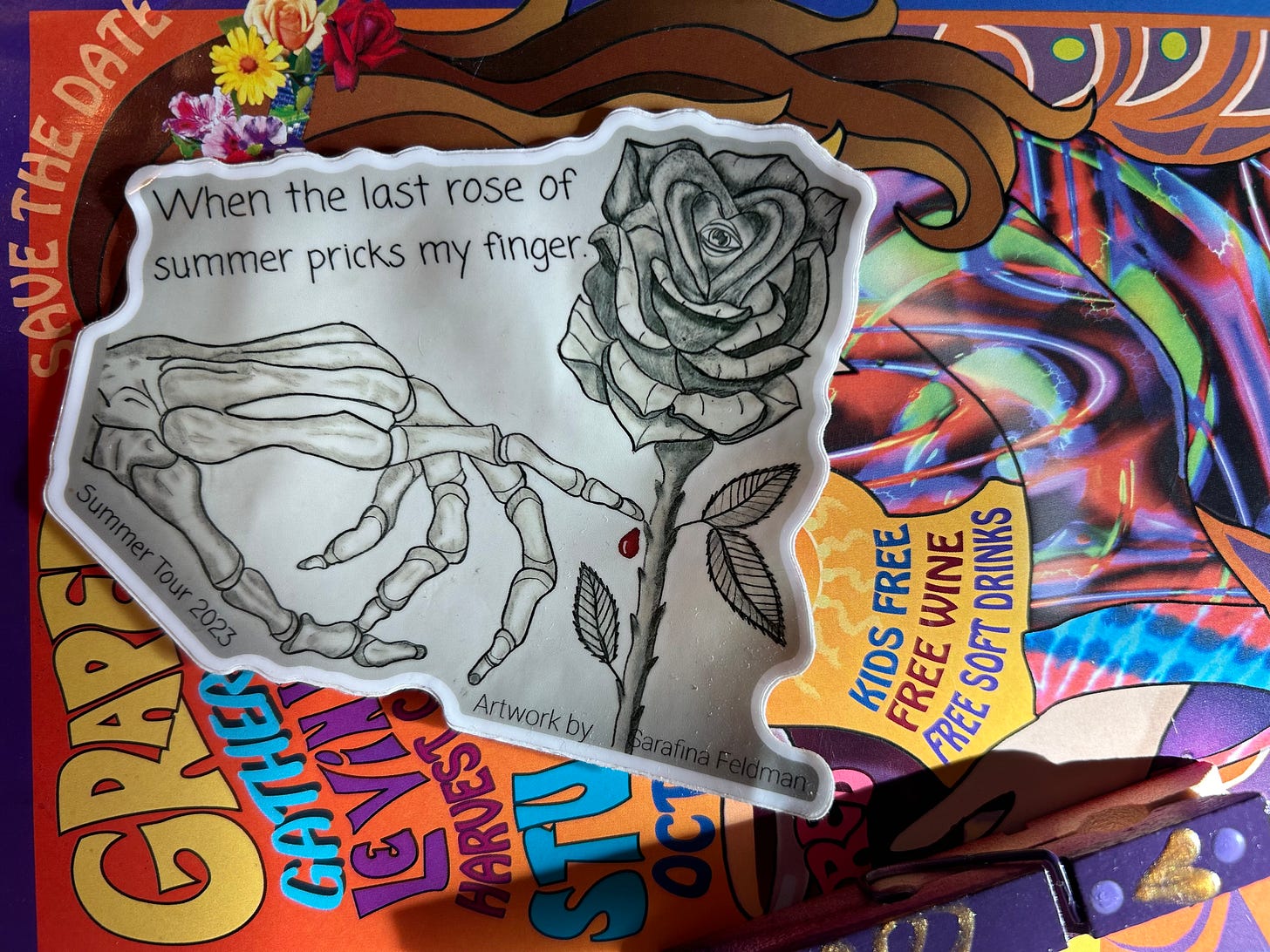

All night people wandered through, young fans moving their hands in figure eights, a gesture disconnected from the music. You could tell who had taken their medicine. Everyone was welcome. When people entered the space they could stay if they danced but otherwise they moved on. Nobody said this out loud. We said it with our bodies. Dance, or go. Don’t talk. We realized that we could have never held the space on our own. When we thanked Dom at the break he shrugged. You know how it is. We’re not fans. We are the Grateful Dead. At intermission the young person who asked us not to talk gave us a handmade black and white sticker to remember summer tour by. We hugged. When the last rose of summer pricks my finger. A spot of red.

More of their friends kept arriving. Miraculously a middle aged butch. She asked if we wanted a lifesaver. Gotta watch out for us old people. We fumbled with the wrapper. Here, I can help. Take two. When a man at the furthest edge of the single row of seats in the section started screaming at the art teacher for smoking near the back wall, the same person sauntered over, lit up, and blew smoke in his face. The nurse appeared. The crew surrounded him while Dom asked us if he’d been in the section all along. Some tension between letting him stay and making him leave. The man had his fists in the air. The young person who gave us the sticker came and stood nearby, a quiet presence. Whatever they did happened fast, almost invisibly. The man left without a fight. He moved up a level and shouted some more, spit flying from his mouth. After a while the sound of his voice dissipated.

It dawned on us slowly that the group had traveled together a long time, in various shapes and permutations, coming together, disbanding and reuniting in the lot. They’d started around the same time Stephanie first came to shows, when they were 17 or 18 or younger, when the Dead was selling out stadiums like this one. They toured hard all the years she didn’t. They just kept going. That’s where they learned how to make a block and hold it, how to take care of each other. Bad stuff could happen on tour. Especially if you were young, if you were a body in a dress, you had to watch out for each other. There were so many assholes who moved up behind you and tried to do whatever, who stole your stuff. We remembered. If you wanted to be with the music, with its sacraments, to get high and be free you had to learn how to move this way, to deal with whatever came up together, to never call on help from security because that would only jeopardize your friends. You had to know who you could trust. Whose liquid dropper. You had to know which parts of the stadium you could dance in. The stadium lessons were particular to Stephanie’s generation, the people who came up after “Touch of Grey.” Clive learned to be careful about tour the other way, living at a collective house where people crashed on their way through town.

Jerry would be so proud, the art teacher murmured as a gigantic steal your face took shape above the stadium, painted there by drones. We pulled out our phones for the first time that night. Everyone in the section was crying a little and gasping. We’d texted old deadhead friends something similar the day before, about the gravitas of Bobby in his 70s. Who would have thought he could hold a stadium like this without Jerry, that the youngest person in the band could become the teacher and pass on what he knew to the next generation of musicians, people Stephanie’s age. Bobby we realized was kind of our dad. And the quiet presence who made the sticker and shushed us, she was kind of our kids.

After “Not Fadeaway,” when the last encore ended where it began on Friday as Clive had predicted, we turned towards each other in excitement. What a fucking show! We might have been friends. We could have known each other. Now we did. Our racing feelings took shape as language. Stephanie did literally thank the art teacher and the nurse for touring. It felt immense, their knowledge, everything they’d learned from the people who toured before them, the small acts that maintained something like a practice, or tradition. There were no guarantees it would continue.

How weird this moment is, Stephanie said, worked up now, flying, our parents dying and children becoming adults. She meant it generally, asserting a cliche about age, the caretaking and loss that defined our predicament in time. One generation getting ready to go on, another coming up, and us in the middle. The nurse caught her eye. My parents are dead. And so, of course, were ours, half of them, but that was beside the point. They’d been alive back then, alive with expectation and demand when Stephanie might have dropped out of school but did not. They’d been alive when Clive was caring for a newborn and driving a delivery truck. Not everyone who went on the road when they were young started for hard reasons. But sometimes you went because your parents kicked you out, because there was nobody waiting for you to come home after work or insist that you go back to school. Sometimes the damages compounded one another. Sometimes you got shown the light, in the strangest of places if you looked at it right. Sometimes you found each other.

The thing about a stadium is that it’s like a puzzle, with enough places to use in ways they were never intended. At the Warfield recently we attempted to hold space for dancing in a building with very few solutions. We felt religious about the things we remembered last summer, ways of being that we’d been reminded of, and tried to hold it down on the floor at a sold out show which if you have been to the Warfield you know is just a dumb idea. And so we played the assholes that night. We applied an idea without having located ourselves in space, which you have to do first in order to leave it behind.

Lately we’ve been encountering crews of people way younger than us who appear to have literal springs on their feet and who know the same things the 90s kids knew, the same things that Clive and Bonnie and their friends did, things that Stephanie and her girlfriend knew: how to find room to move wherever they go. They are wherever we want to be, free and resplendent, their genders slipping off. They whip their hair back and forth. They move in wild packs and light fires on the sidewalk. We saw them at Ashkenaz last fall at a China Dolls show. They are really good dancers. They live for it. We ran into the Sonoma county version of this crew at Stafford Lake Park in Novato last August. We thrashed with them in the dirt and grass. They are almost always on the outskirts which is the other lesson we’ve been relearning lately. You don’t need to see really, or be that close. You just need room to move. You need to keep an eye out for each other. And to not talk while the music is playing. That’s kind of it.

For anyone else not buying tickets to the Sphere we hear Terrapin Clubhouse will be announcing their summer 2024 lineup soon. There’s the Valentine’s Day show coming up next week, China Dolls in March, and Melvin Seals & JGB at The Guild. And omg a friend just sent us this map of all the tribute bands, a site created in the days of a gentler web, rendered foolish now by time. It’s a circus out there.