When I finally decided to get the bad tattoo on my ankle redone I kept telling Francisca Silva that the butterfly with mottled greenish purple wings was 20 years old, inadvertently revising the tattoo and myself down by a decade. No wonder it looks so bad, I thought later.

For a few hours after I got it in 1993 the bad tattoo pleased me. It matched a larger piece my girlfriend got the same day, a jester and Shakedown Street figure with long hair, bells on their toes, and a vest open to reveal an androgynous chest. The tender mix of feelings that informed my desire to rhyme with her body probably included the mute wish for her coolness to rub off on me in the same shades of burgundy, deep green, and turquoise. Almost immediately my body rejected the colored ink. The skin turned hot, oozing and scabbing and cracking and scabbing over again, leaving behind a faded shape that only partially evoked the image chosen from the wall of a tattoo studio in Spokane that I cannot now remember the name of.

When the bad tattoo finally healed I felt embarrassed in the usual way. This eventually coddled into a perverse sense of pride after I heard someone in the late aughts, a comedian or radio DJ, make fun of Zooey Deschanel for being the kind of twee girl who would get a butterfly tattoo on her ankle. Something inside me blushed, then shrugged. I didn’t feel like a twee white girl with bangs who would get a butterfly tattoo on my ankle, the sort who would appear a few years later on Collier Meyerson’s blog Carefree White Girl, and yet there it was. I could look down and see it. You don’t get to choose the forms of misrecognition that proceed from whatever identities you find yourself assigned to, no matter how dissonant their constructions may feel, how far outside their ways of being in the world you may imagine your own.

The bad tattoo could not be mistaken for being bad on purpose. It did not look good in any light. It barely even looked like a butterfly. The bruise colored blob announced itself loudly above my ankle bone, drawing attention to a part of my body I actively disliked and yet had managed to accentuate. The bad tattoo pained me as all bad drafts do, when the thing you have written does not in any way match the idea in your head. It did not say any of the things I might have wanted it to at the time: it did not scream lesbian nor was it an argument against the Christian right or a rebuke of the highly organized white supremacist groups in northern Idaho just 45 minutes east of the campus where I’d chosen to attend college because it was the most liberal of the religious schools that my family would pay for. As I got older it looked worse, bearing out all the things you know about bad tattoos. Set against professional clothing the tattoo trolled me. It shouted aging party girl, failed Deschanel, big dummy.

I teach college students for a living and have over the years witnessed tattoo fashions come and go: Celtic knots, Chinese characters, long cursive lines of script from Harry Potter, stick and poke triangles, intricate botanical drawings. Whenever I thought about getting the bad tattoo redone I imagined the dated aesthetic I would carry into the future, a palimpsest of what was sure to be another bad draft. Cover ups are always larger than the original design and I didn’t love the idea of making the bad tattoo even bigger. I briefly considered laser removal but the lasers weren’t very good yet, plus I had developed a weird commitment to the bad tattoo. Look at this dumbass thing I did. I am not a cool person.

The older I got the less amused I felt about my body going around announcing a carefree feeling I had never actually experienced, the same way I aged out of the kick I used to get in my late 20s when purchasing coffee for the only woman on the executive team at my first office job. I spent much of my 40s in a protracted struggle with higher education: the massive amounts of debt that it produces, its elite of which I am not and will never be part, and its reliance on underpaid adjunct labor, which I am. This agonistic decade included some epiphanies, too, each its own long story. A fire forced us out of the house we rented below market for decades. Shortly thereafter I finally got diagnosed with endometriosis; surgery alleviated decades of pain endured in that same house. We moved into a new neighborhood and entered into, there is no other way to say this, a relationship with a plant spirit who lives here, where the weird final end of my youth unfolded, coinciding with the pandemic and imparting intense sympathy for every 13 or 14 year old stuck at home going through it. Shortly before I turned 50, the idea of reworking the tattoo presented itself again.

When I told a version of this story to Silva’s wife Hillery Sklar as I waited for my appointment to begin, she pointed to a tattoo near her wrist, a small blue orb and one detail in a sleeve that started with the desire to rework her own mistake from the 90s. Sklar and Silva felt familiar, people I could have met at a party years before. I first learned about Silva’s work when poet Stacy Szyzmacek posted that Silva was going to be in Oakland. I’d been corresponding intermittently with Szymaszek for a few years and even though we’ve never lived in the same city we do share friends and scenes and a generational location in common. Sometimes while reading their poetry the sense of shared concern is so strong that it evokes a word like mystical. The experience is a little bit like the Bernadette Mayer poem that I have loved so much and witnessed in my lifetime become anthemic, as it should be, “the way to keep going in Antarctica,” except if Antarctica was being a poet, having a body, aging inside of it. I guess that is, in a way, the definition of Antarctica.

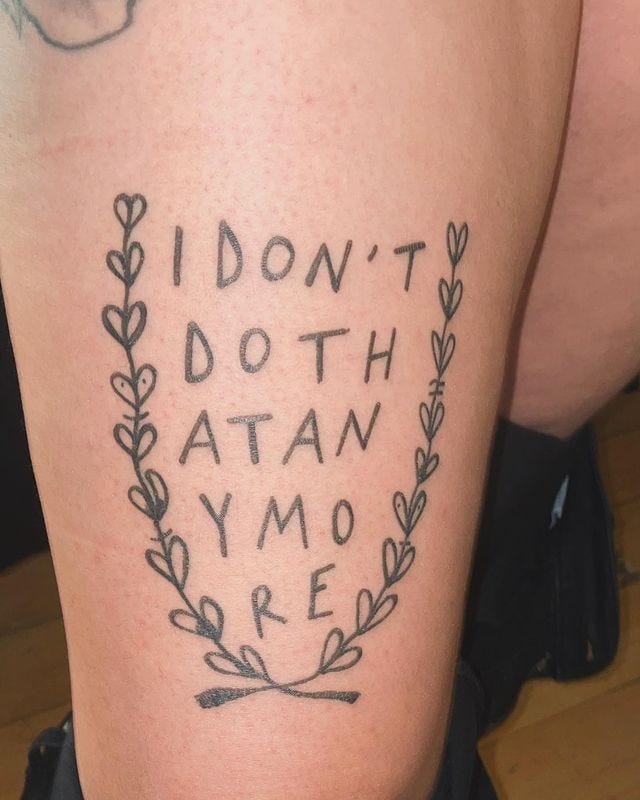

When Szymaszek shared Silva’s post I felt intensely drawn to their work, the opposite of twee, thick somehow, even when detailed, a quality they called BRUTAL MINIMALISM in this 2018 interview. Silva breaks words into letters, stacking them in distinctive columns. One result is phrasing that challenges the eye, asking its reader to go slowly and reassemble words from their parts. Many of my favorite poets in New York follow Silva, who is also a poet, and you can see why. Browsing their page I noticed a few tattoos of the phrase SPIRITUAL HARDCORE. I dmed for an appointment.

There’s a mantra I have started working with when in the space of particular plant medicines. It sounds trite when I write it down, so I won’t. My plan was to get the butterfly re-inked, rather than covering it up, and then add a word around the edge, drawn from the mantra but scrambled into parts. Silva’s style would allow me to work with the mantra while also keeping it private. A kind of revision of my younger self, by someone, me, older and more thoughtful now.

I didn’t want letters placed under the original design, on the ankle bone where I knew the pain would be worse. I kept referring to the ankle bone as “down there.” When Silva drew the word on my leg, it formed a crown above the butterfly. I was directed to a mirror to make sure I wanted these lines rendered permanent, where I glanced at the shape and loved it. On the table it hurt as much as and less than expected. I focused on my breathing and imagined the feathers of my nervous system laying flat. Afterwards I finally understood the appeal. Maybe I’ll start up with tattoos in midlife, I told Claire in the car a few days later. Yeah, you’re going to live to 100, she laughed.

When I sat up, I saw it. Scrambling the word had revealed another, unintended meaning.

At home I felt too small for the temper running through my body, myself against myself, remembering that quick glance in the mirror, yes, it looks great, handing the experience over to an expert. I should have just handed it over completely, should not have tried to have an idea. I texted Trisha, who has a lot of tattoos. I texted Gina, also on the cusp of turning 50. A new idea arrived: I could add more letters, more information that would further scramble and perhaps undo the clarity of the unintended word that had appeared there as if by bad magic. More letters might even evoke the word I had originally intended? I workshopped these ideas with friends, and inexplicably, my mother. The addition of an asterisk that would have directed the eye where to begin reading was rejected for the same reason that it drives me over a wall when poets explain their poems away before reading them aloud.

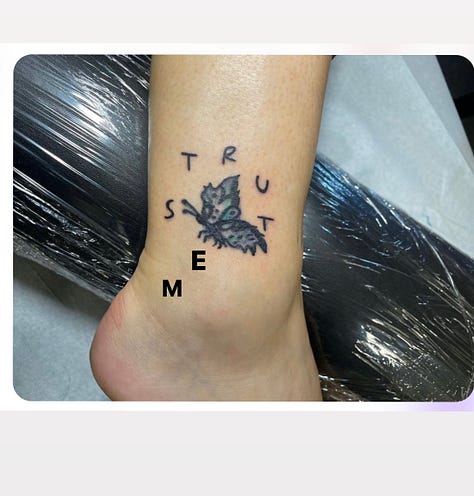

Talking to Sklar again the next day, I confessed the reason for my return and the minute I explained she saw the word, too. Strut. Silva, who works in and between three languages, hadn’t seen it because she wasn’t familiar with the word so Sklar and I did our best to describe what it meant: showing off, or walking with pride, something you do if you think you are hot stuff. Silva, bemused, wondered if this wasn’t in fact a great word to have unintentionally put on my body. We talked about aging. Did anyone ever really change? I was never going to be cool. But I had returned and asked for what I wanted, which wasn’t nothing. We laughed about the ankle bone. Had I not insisted on avoiding the pain of tattooing this part of my body, the word would have appeared differently. As Silva added two more letters, Sklar stood by the table and performed Reiki, her hands on my legs, the moment unexpectedly hot and deeply sweet. Silva said the revision was on the house.

I drafted this story way before Pluto entered Aquarius, before we were so deep into this wild year, my 50th, which I share with a bunch of Bay Area arts orgs also in the process of revising themselves. I still want to understand why 1974 in particular witnessed such a sharp rise in Bay Area non profit arts funding, most of it long gone, surely another long story. I thought this one, about the bad tattoo, might be a useful way to reflect on our writing process here, which is so much like talking. The unexpected sweetness of working in groups of two or three, the patterns that repeat themselves.

Gertrude Stein said famously that there is no such thing as repetition, only insistence. The same could be said of the bad tattoo. I will never be cool. Maybe there is no such thing as revision, only writing. No such thing as writing, only talking. Right now we’re talking a lot at our house about the Sunday Daydream Volume 3 show, which paid homage to the 50 year anniversary of the Grateful Dead’s Hollywood Bowl performance on July 21, 1974, a few months before what would be the first in a long series of farewell tours followed by fervent reunions. We’re still talking about Volumes 1 & 2 before that, at the Bruns, home of Cal Shakes, a revision of what is possible in that space. My ambivalence on the subject of the Sphere shows, winding down now, is as strong as the next guy's but about Terrapin Crossroads I am enthusiastic to the point of provocation. If you live nearby, may I suggest not missing volume 4 on August 18? 💎